Tetsujin 28-gō and The Transforming Heroes of the 1970s

In 1956, five years after Osamu Tezuka’s Ambassador Atom, the serialization of another founding manga work in the robot genre began: Mitsuteru Yokoyama’s Tetsujin 28-gō.

Tetsujin 28-gō, a Giant Weapon in Human Form

As seen previously, while Astro Boy was effectively an artificial human, Tetsujin[fig.1] is a weapon that cannot think on its own, and can be considered one of the manned, or boarded giant robots that were ubiquitous in the 1970s. In addition to this fundamental difference, Tetsujin is intentionally differentiated from Astro Boy as well. Unlike the childlike form of Astro Boy, Tetsujin takes inspiration from the Hollywood movie Frankenstein, in which a manlike monster kills people while being manipulated by a mad scientist (1), and is presented as a roaring giant. The story uses the boy detective format, and unlike the manga version of Astro Boy, which was strongly thematic—including its self-referential nature with regards to the manga genre itself—the series is designed to be easily digested by young male readers.

Fig.1. Tetsujin 28-gō by HIKARI-PRODUCTION/EIKEN

Fig.1. Tetsujin 28-gō by HIKARI-PRODUCTION/EIKEN

As identified in the previous step, wartime scientific realism was the source of the scientism in Tezuka’s work, and the contemporary drama of Tetsujin 28-gō is even more directly linked to that memory. Tetsujin is military robot developed by Professor Shikishima, a Japanese Army scientist, “at the end of the Second World War” (the title of the first chapter), and the name 28 must originate from the American B29 bombers that were often used in airstrikes against Japan towards the end of the war.

Much like with Astro Boy, Tetsujin’s activities imparted a sense of omnipotence on its readers and viewers though the medium of a body that was artificially strengthened and made gigantic. In particular, the size of Tetsujin was like an adult’s body to children, and as was made clear in subsequent works, represented the body of a father. However, though we might describe this body as that of an adult, this is not to say that the work Tetsujin 28-gō is free of the Astro Boy Problem of robots that are not permitted to grow up. The hero, Shotaro Kaneda[fig.2], borrows the body of the weapon of war—the body of an adult or father—only when he uses the remote control, remaining a boy, meaning that growth actually is forbidden. That the “shota” part of his name became the slang term for the object of shōnen-ai is also symbolic (2).

Fig.2. Shotaro Kaneda, the first “Shotta”

Tetsujin 28-gō, vol.12, p. 7, by Mitsuteru Yokoyama, Kobunsha-Bunko Comic Series, 1996

Fig.2. Shotaro Kaneda, the first “Shotta”

Tetsujin 28-gō, vol.12, p. 7, by Mitsuteru Yokoyama, Kobunsha-Bunko Comic Series, 1996

The Great Transforming Hero Boom

This is how the postwar robot genre began, with the first Tezuka works (represented by Astro Boy), Tetsujin 28-gō, and their anime adaptations as the founders (3). In 1966, the kaijū boom swept the nation with the broadcast of the live-action giant hero series Ultraman, but in the 1970s, robots and cyborgs became children’s heroes once again. In the EXPO’70 in Osaka (around 64 million 21 thousand visitors), Osamu Tezuka designed the “Fuji Baking Robot Building.” The momentum for this came from Kamen Rider (1971), a live-action work that included the manga artist Shotaro Ishinomori among the production staff, and Mazinger Z (1972), an anime work created from an idea by Go Nagai, a former assistant of Ishinomori’s (4). The former established the new key concept of transforming, while the latter established boarding, both of which would become staples of the genre.

Ishinomori[fig.3] was an assistant of Osamu Tezuka’s, and his talent was quickly recognized.

Fig.3. Shotaro Ishinomori (1938-1998)

Photo credit: The Mainichi Newspaper Co.

Fig.3. Shotaro Ishinomori (1938-1998)

Photo credit: The Mainichi Newspaper Co.

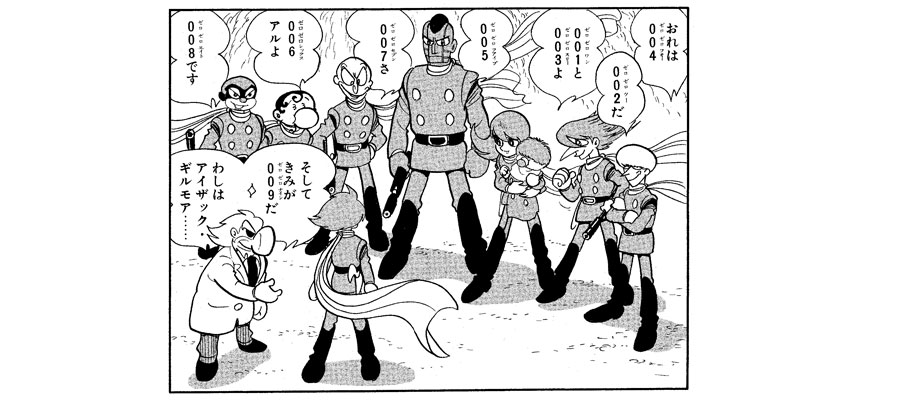

While involved with the production of the anime version of Astro Boy, which began broadcasting in 1963, he began work on Cyborg 009 [fig.4] in 1964, a manga series which concerned a group of nine cyborg soldiers of different nationalities—the same number of members as a baseball team. Though incomplete due to his death, the work is representative of Ishinomori, and has been the subject of a number of remakes into the 21st century. Unlike Astro Boy and Tetsujin, the members of 009 were originally living humans, who were surgically altered by an evil organization—the degree of mechanization varying between members—becoming the cyborgs mentioned in the title. The hero, 009 (also known as Joe Shimamura) is depicted as being very young, but received the surgery when he was 18, and in that he has a romantic relationship with the heroine, 003 (also known as Françoise), the target age range is set relatively high.

Fig.4. Nine Cyborgs (No.001 ~ No.009) and Dr.Gilmor

Cyborg 009, vol.1, p. 83, © Shotaro Ishinomori, ISHIMORI PRODUCTION INC, Akita-shoten Sunday Comics, 1966

Fig.4. Nine Cyborgs (No.001 ~ No.009) and Dr.Gilmor

Cyborg 009, vol.1, p. 83, © Shotaro Ishinomori, ISHIMORI PRODUCTION INC, Akita-shoten Sunday Comics, 1966

In 1971, Ishinomori again incorporated the transforming idea in cyborg works by supplying ideas for Toei’s seminal tokusatsu program Kamen Rider [fig.5], and also drew the manga version at the same time as the televised version.

Fig.5. Kamen Rider

Cover page of Kamen Rider Showa Saikyo Densetsu, Toei

Fig.5. Kamen Rider

Cover page of Kamen Rider Showa Saikyo Densetsu, Toei

After this, Toei and Ishinomori went on to produce Jinzō ningen Kikaider (1972), which was modeled on Pinocchio, and Himitsu sentai Gorenger (1975), which concerned a team of five heroes, thereby building the foundations of tokusatsu hero work: live action, life-size characters, and transforming. Even now, Rider and sentai series are produced yearly—although the former had a break—and enjoy steady popularity.

Transforming into heroes is a concept that predates Rider, and the Ultraman [fig.6] series in particular serves as a representative example of this. Ultraman is an alien who normally takes on a human appearance, but in times of danger, uses an item—Ultraman’s Beta Capsule, Ultraseven’s Ultra Eye—to transform into a gigantic hero and do battle with enemy kaijū monsters.

Fig.6. Ultraman Statue at the Ultraman Street in Tokyo (Tsuburaya Production)

Fig.6. Ultraman Statue at the Ultraman Street in Tokyo (Tsuburaya Production)

On the other hand, the later Kamen Rider is a life-sized, altered human, who uses a phrase and a special pose to transform (5). Children would sit in front of television sets with rapt attention, waiting for the moment that their hero would transform. The two major series have differences in their settings—for example, Ultraman is a member of an organization to defend the Earth, while Rider is a lone hero—but both programs share the same scenario development taking place over 20 broadcast minutes: enemy appears → ally is in danger → hero transforms → surprise victory. This is what has become the transforming hero format.

In Ultraman, the name of the organization to defend the Earth is the “Scientific Special Search Party,” and Rider is an altered human, but like in the case of the anime version of Astro Boy, the television program is fundamentally a series for children, and it is hard to find thematic elements in the technology within the work. The transformations themselves were never necessary for combat, and exist to serve as highlights in the stories and to commercialize the work, for example through toy transformation belts. However, the existence of cyborgs in Ishinomori’s original manga can be considered an important statement.

The Sorrow of Ishinomori-style Cyborgs and the Identity of the Japanese

The heroes depicted in Ishinomori’s work such as Cyborg 009 and Kamen Rider have had their bodies mechanized by an enemy organization —which can be considered a violation or a form of rape— and suffer the sorrow of having their identities as people stolen from then. As such, they straddle the line between human and machine (non-human), and good and evil, suffering an existential conflict. Much as Ambassador Atom was an allegory of Japanese-United States peace, if one were to link this dilemma with its time period, then perhaps one could match up Ishinomori-style heroes with the postwar Japanese people who make up the hybrid entities (6) in the process of the Americanization of Japan, its becoming a technologically-driven country, and in particular, its becoming a major player in the robotics industry.

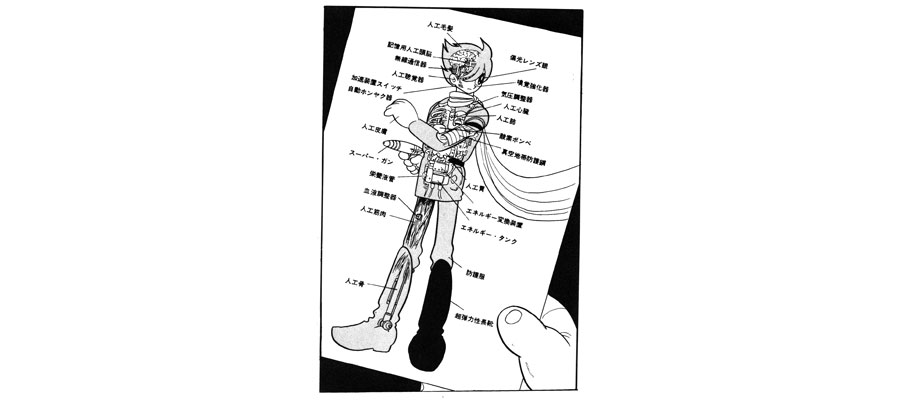

It is also symbolic that Joe Shimamura was already a half-Japanese boy before he was made into a cyborg[fig.7]. Eventually, in the 1980s, an Oriental, not necessarily Japanese, image was added to cyborg culture and robot engineering from the outside, resulting in representations and statements such as Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982), Styx’s hit song “Mister Roboto” (1983), and the Chiba City that appears at the start of William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984). Furthermore, as Takayuki Tatsumi points out, Japanese science fiction authors and figures such as Masamune Shirow and Mamoru Oshii reinforced this trend from within. The postwar Japanese people were virtual cyborgs, imitation Japanese.

Fig.7. Joe Shimamura, No.009-cyborg, Click to take a closer look

Cyborg 009, vol.1, p. 119, © Shotaro Ishinomori, ISHIMORI PRODUCTION INC, Akita-shoten Sunday Comics 1966

Fig.7. Joe Shimamura, No.009-cyborg, Click to take a closer look

Cyborg 009, vol.1, p. 119, © Shotaro Ishinomori, ISHIMORI PRODUCTION INC, Akita-shoten Sunday Comics 1966

Additionally, with Devilman (1972-73) —as the title implies, the hero was a man who had obtained the power of a devil— Go Nagai, formerly an assistant of Shotaro Ishinomori, inherited (and perhaps completed) the Ishinomori-style hero who straddled the line of good and evil.

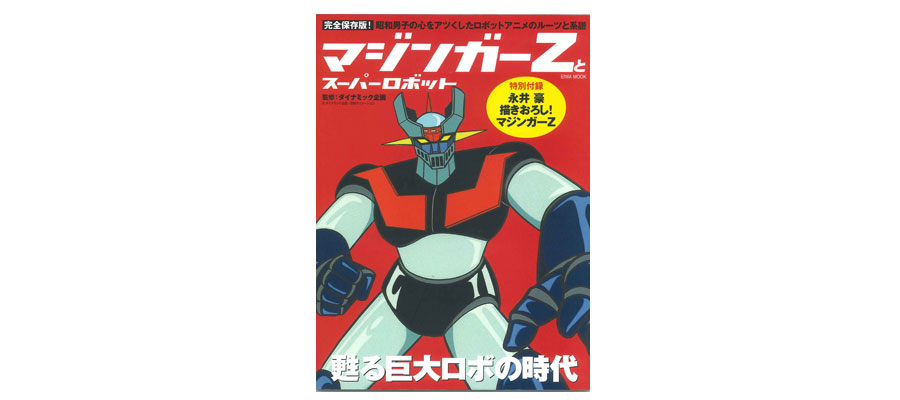

And he also created Mazinger Z [fig.8] (1972), the founding work of the super robot genre that took the 1970s by storm alongside the transforming hero genre. Unlike Tetsujin 28-gō, in which there was a system to remotely control the giant robot, in Mazinger Z, the hero Koji Kabuto established the trend of boarding the giant robot (7).

Fig.8. Mazinger Z Click to take a closer look

Mazinger-Z and Super Robots edited, cover page, by Dynamic Production, Eiwa-shuppansha 2015

Fig.8. Mazinger Z Click to take a closer look

Mazinger-Z and Super Robots edited, cover page, by Dynamic Production, Eiwa-shuppansha 2015

Like the boarding-style robots featured in the Hollywood movie Pacific Rim (2013), which was filled with homages to Japanese kaijū works, the paranoid attachment to this idea is uniquely Japanese. However, at the same time, that the acceptance of boarding-style giant robot anime served as the catalyst for an explosive Japanese animation boom overseas in the 1980s would suggest that there is a universality to its charm. Where might we find the reason for this?

Comments