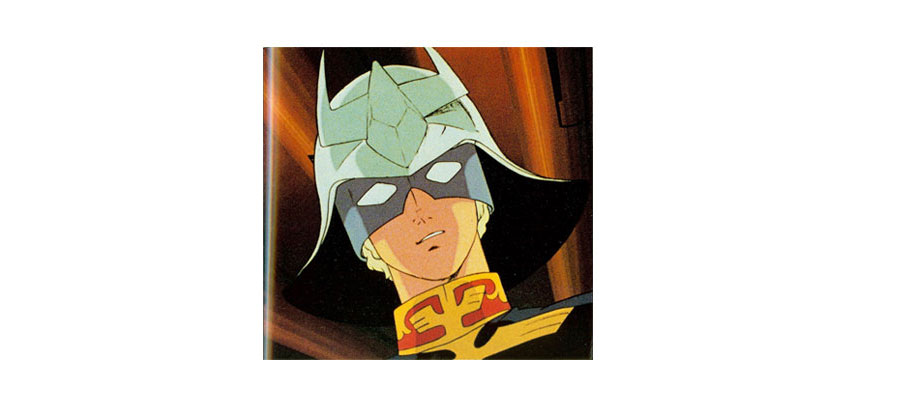

create something that would stand out from the existing titles, resulting in the production of the original robot anime Brave Raideen (1975). Sunrise was also responsible for the creation of a string of robot anime series such as Chōdenji Robo Combattler V (1976, a Toei project), and the company’s achievement gained it the sponsorship of the toy company Clover. Director Yoshiyuki Tomino and other staff members who would work on Gundam would then go on to create the original works Muteki Chōjin Zambot 3 (1977) and Muteki Kōjin Daitarn 3 (1978), which are still highly praised to this day, before embarking on the preparations for Gundam. In fact, the popular, handsome enemy character from Gundam, Char Aznable[fig.2], was based on Raideen’s Sharkin(2), and to differentiate the series from Mazinger Z, the design of Raideen (the starring robot, patterned after a samurai warrior) was carried over into Gundam as well.

Fig.2. Char Aznable

by Mobile Suit Gundam Kiroku Zenshu, vol.1, p. 82, (c)SOTSU・SUNRISE, 1979

Fig.2. Char Aznable

by Mobile Suit Gundam Kiroku Zenshu, vol.1, p. 82, (c)SOTSU・SUNRISE, 1979

The story of Gundam is based on Jules Verne’s Two Years’ Vacation (1888) (3), and can be said to be a space version of that novel. In a future where mankind has succeeded in emigrating to space, one space colony declares itself an independent state called the Principality of Zeon (4), and starts a war of independence against the Earth Federation. Young children from another space colony, Side 7, are embroiled in the conflict, and are taken aboard the Federation warship White Base, where they experience the war, spanning one year, largely as soldiers. The main character is the naïve young boy Amuro Ray [fig.6], who was markedly different from the previous hotheaded heroes of the genre. By coincidence (naturally), he becomes the pilot of the cutting-edge human-shaped weapon Gundam, created by his father, and manages to survive the war. His rival, meanwhile, is the Zeon military’s ace pilot, the aforementioned Char Aznable, but rather than simply being a member of an evil organization like the rivals in other works, his origins contain hidden secrets and tragedy.

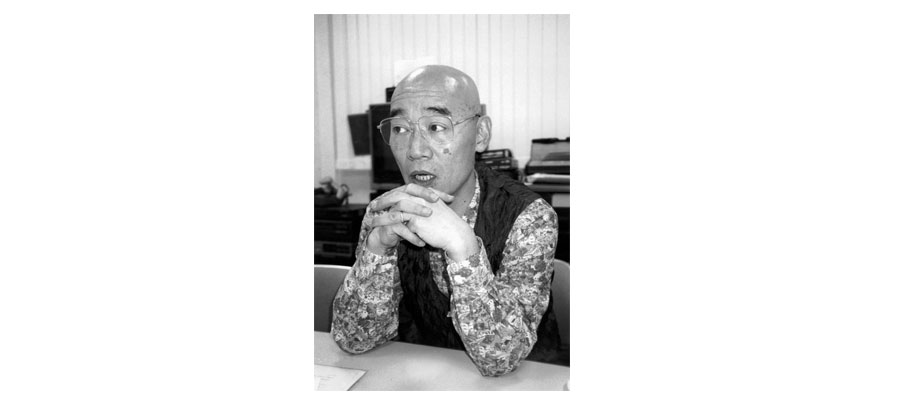

Gundam also had the role of being an advertising program to promote the sales of products from sponsoring toy companies, and even the leading robot of the series is able to transform and combine despite this having no meaning at all on the battlefield. However, despite being bound by the restrictions of robot anime for children, the talent led by director Yoshiyuki Tomino[fig.3] accepted those restrictions as professionals, and rose to the challenge of creating a true human drama within those boundaries, thereby confronting the robot anime that followed with its antithesis. As a whole, this may have been a challenge to Tezuka’s Astro Boy Problem.

Fig.3. Yoshiyuki Tomino ( 1941- ) - Photo credit: The Mainichi Newspapers Co.

Fig.3. Yoshiyuki Tomino ( 1941- ) - Photo credit: The Mainichi Newspapers Co.

Anime’s Limitations and Reality

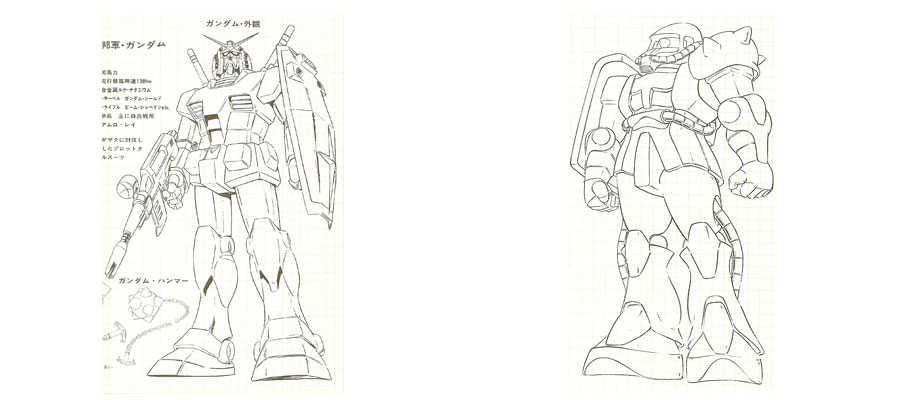

The core of this rebellious spirit is none other than Yoshiyuki Tomino (who debuted at Mushi Production), and Gundam was born from his genius ideas. Tomino would later introduce the mysterious plot element of Newtypes (apparently, even the staff at the time did not understand most of the concept) in the latter half of the series, bringing it a strong thematic element. Meanwhile, Kunio Okawara, who defined the role of mechanical designer in anime works, designed mecha (i.e. robots) that could be made three-dimensional in real life while under a tight production schedule and other difficult conditions (5). In the case of the Gundam, the main mecha, he avoided the “cylindrical legs and rectangular parts of Mazinger Z”, aiming instead for “a form with parts that could imaginably belong to a human body; calves, for example” (6), and the human-shaped weapon that realized this goal was not called a robot, but a mobile suit[fig.4]. In particular, the mass-produced Zaku[fig.5], enemy robots with a “monoeye” (a Tomino idea), had an unusual design and the military sound of “mass production,” and could be said to be the real charm of the work (7).

(Left) Fig.4. The Mechanical Design of Gundam, by Kunio Okawara, Click to take a closer look

Mobile Suit Gundam Kiroku Zenshu, vol.1, p. 134, (c)SOTSU・SUNRISE, 1979

(Left) Fig.4. The Mechanical Design of Gundam, by Kunio Okawara, Click to take a closer look

Mobile Suit Gundam Kiroku Zenshu, vol.1, p. 134, (c)SOTSU・SUNRISE, 1979

(Right) Fig.5. The mass-produced Zaku, Click to take a closer look

Mobile Suit Gundam Kiroku Zenshu, vol.1, p. 138, (c)SOTSU・SUNRISE, 1979

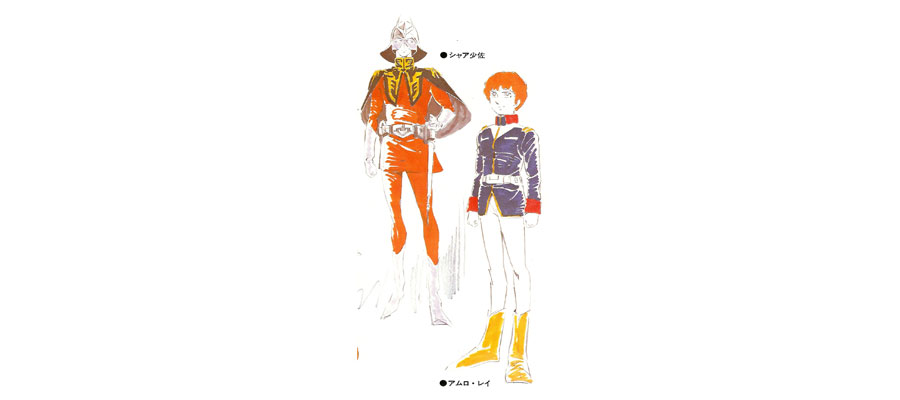

Yoshikazu Yasuhiko, the chief animator and character designer (and yet another Mushi Production alumnus), approved of the human drama and coming-of-age story Tomino was working toward, and designed “humans, not characters turned into codes”[fig.6] (8) that could hold up to the drama.

Fig.6. The Character Design by Yoshikazu Yasuhiko (Char and Amuro),

Click to take a closer look

Mobile Suit Gundam Kiroku Zenshu, vol.1, p. 86, (c)SOTSU・SUNRISE, 1979

Fig.6. The Character Design by Yoshikazu Yasuhiko (Char and Amuro),

Click to take a closer look

Mobile Suit Gundam Kiroku Zenshu, vol.1, p. 86, (c)SOTSU・SUNRISE, 1979

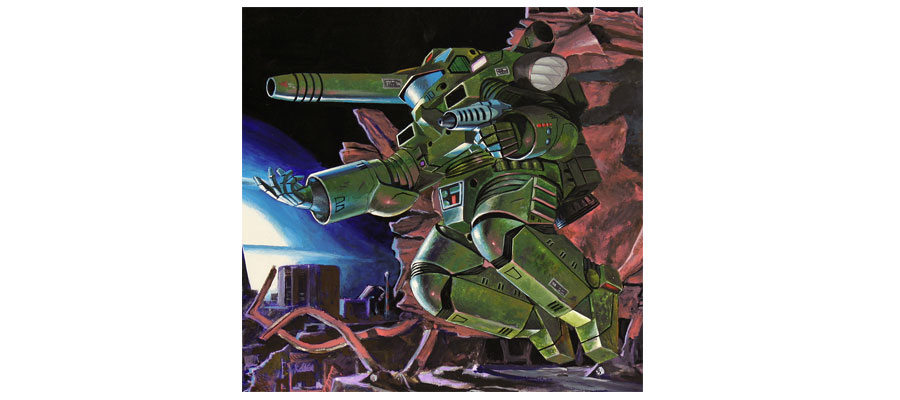

Reality was also sought in terms of technology. The technology found in Mazinger Z and other robot anime of the 1970s sought to serve a science fiction role, but stopped at a superficial level, while Gundam carried on the science fiction study of Space Battleship Yamato (1974) (9), and with the assistance of Studio Nue (10), which had already garnered acclaim, incorporated a new level of reality compared to the robots that came before. The background for this revitalization of the genre, meanwhile, is the fact that the anime audience had grown older. For example, Gundam is influenced by the powered suits drawn by Studio Nue’s Kazutaka Miyatake and Naoyuki Kato for the illustration of the Japanese publication of Robert A. Heinlein’s Starship Troopers[fig.7] (1959).

Fig.7. A picture in the Japanese version of Uchu no Senshi (c) Kazutaka MIYATAKE, Naoyuki KATOH / Studio NUE

Fig.7. A picture in the Japanese version of Uchu no Senshi (c) Kazutaka MIYATAKE, Naoyuki KATOH / Studio NUE

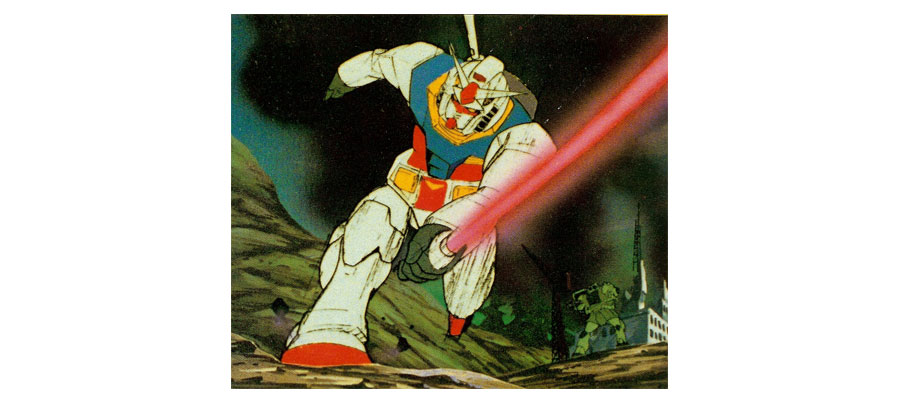

Naturally, the Minovsky particles that nullify radars—somehow making space brawls between robots legitimate—and other features are pseudoscience, but these features support the world-building of the work as assumptions of space-age science fiction, and would be used in a variety of settings within the work. Incidentally, the beam saber[fig.8] wielded by the Gundam was inspired by the lightsabers of Star Wars (a big hit in Japan as well), which in turn, as is common knowledge, was originally inspired by Japanese samurai movies. Whatever the case, one can see that the realism of weapons from during the Pacific War has been revived in fictional battlefields (11).

Fig.8. Gundam wielding Beam Saber - Mobile Suit Gundam Kiroku Zenshu, vol.1, p. 15, (c)SOTSU・SUNRISE, 1979

Fig.8. Gundam wielding Beam Saber - Mobile Suit Gundam Kiroku Zenshu, vol.1, p. 15, (c)SOTSU・SUNRISE, 1979

At the start of its broadcast run, Gundam was not particularly popular due to its the science-fiction setting and drama, and the difficult-to-understand concept of Newtypes, but after its broadcast run ended (cancelled due to low viewership), it had gained such popularity that plastic models (nicknamed “Gunpla”) of the Zaku and other giant robots were difficult to obtain, and the series began to be reevaluated. Tomino and co.’s attempt was successful, and Gundam would set robot anime on a new course: the “real robot” route.

Comments