Why was Hatsune Miku successful?

In the summer of 2007, an idol singer appeared on a Japanese video-sharing site. Her voice and the illustration of her standing pose met with a feverish response, and soon, a huge, internet-based movement began.

She appeared on small screens singing, twirling leeks, and dancing, but she did not exist as a real person. Her name was Hatsune Miku—often given thus in Japanese order, with “Hatsune” derived from the words for “first sound,” and “Miku” meaning “future”—and she was a virtual idol born of cutting-edge audio technology. And while being a piece of music software, her appearance and reception are also firmly rooted within Japanese subculture.

As discussed in the previous step, Hatsune Miku is a work of desktop music software that outputs vocal audio, released by the Sapporo, Hokkaido-based company Crypton Future Media on August 31, 2007.

In addition to her real form as a piece of software that produces an artificial singing voice, it is also important to consider her body and her story, which are the illustration of her on the CD-ROM package and the absolute minimum background information provided with it (age: 16, height: 158 cm, weight: 42 kg). Users create cover songs and original songs performed by her image, and mainly post them to the video-sharing site Nico Nico Douga, with fans who view these videos cheering her on with scrolling text on the screen (this feature differs from those available on YouTube). As her popularity erupted, she went on to be active in a range of media, such as games and live concerts.

Furthermore, Crypton and other developers produced countless Vocaloids in addition to her, and eventually, artificial songstresses started to appear all over the world, singing in various languages (for example, Alys[fig.1] in France). And with developments such as the ability for anyone to create their own vocal outputs using free software, ever since the success of Hatsune Miku, Vocaloids have become an entirely new musical genre overnight.

Fig.1. Alys in France,

Design d’ALYS créé par Saphirya, Marque ALYS déposée par VoxWave, Tous droits de reproduction réservés par VoxWave

Fig.1. Alys in France,

Design d’ALYS créé par Saphirya, Marque ALYS déposée par VoxWave, Tous droits de reproduction réservés par VoxWave

A Brilliant Connection to Anime Culture

As you will see in the following step, people have long had fetish-like desires toward voices and have dreamed of artificial singing. The technology that created today’s Vocaloids began development around 1990, and in fact, Vocaloids existed years before Hatsune Miku’s appearance (1). But why did Hatsune Miku gain such outstanding popularity? Of course, the technology did progress closer to more natural singing. But aside from that, Crypton had an ingenious plan that truly grasped the essence of this technology: it linked Vocaloids to anime culture. Vocaloid output is created by sampling real human voices. On the topic of Hatsune Miku’s voice actress, Hiroyuki Ito of Crypton says, “I thought of going for something totally different from the polished voices of narrators and newscasters. To be blunt, I was looking for a so-called Lolita voice,” (2) and so the company employed Saki Fujita[fig.2], who had worked in anime previously. Additionally, Miku was given a body that complemented this voice. This was the bishōjo body established in the manga and anime fields—to repeat, a body that can be traced back to Osamu Tezuka’s codified bodies. Wataru Sasaki, one of the fathers of Hatsune Miku, says, “Some things use attraction to draw you in before showing you their actual substance, for example the details of illustrations or the plot of erotic games, and Hatsune Miku is the result of our attempt to do that in our own way” (3). In other words, Crypton used moe to bring people into contact with the true value of the latest technology. And despite moe being what it is, they took care in selecting the illustration.

“The reason why we chose Kei as the illustrator for Miku is that the pictures drawn by what you would call famous moe-style illustrators include symbolism like blushing of the skin that don’t suit Vocaloids, and I wasn’t personally interested in that either. Kei’s illustrations, on the other hand, have elements of mechanicalness and darkness, which I thought suited Miku.” (4)

This is not just a superficial thought that the software would sell simply by representing it with anime imagery. Because the software is a “[synthesizer] that can only produce one sound” (that is Hatsune Miku’s voice performed by Saki Fujita) (5), the illustration is based on the Yamaha DX-7 synthesizer[fig.3], a famous model of the 1980s—Hatsune Miku’s green hair is also based on the colors of the synthesizer. To put it another way, one can say that in addition to her voice, Hatsune Miku’s body is also a personification of electronic instruments—a bishōjo representation.

Fig.3. YAMAHA Synthesizer DX-7 (a picture from wikipedia)

Fig.3. YAMAHA Synthesizer DX-7 (a picture from wikipedia)

“Hatsune Miku as a Hub”

The combining of the latest audio technology and anime culture gave birth to magic, and trends on the Internet also assisted Hatsune Miku. Nico Nico Douga[fig.4], a video-sharing site that started operation in 2006, was the perfect stage for Miku.

Fig.4. Nico Nico Douga screenshot, captured on October 1st, 2016

Fig.4. Nico Nico Douga screenshot, captured on October 1st, 2016

The majority of users were amateur desktop music enthusiasts, and by gaining this “playground,” they could post their work for free at the click of a button and share it with tens and hundreds of thousands of viewers. At this video-sharing site, one can show pictures and videos of Miku as well as play music. For Miku—linked to anime culture—this system was essential. Furthermore, Crypton’s attitudes toward copyright (the company does not prohibit the publication of derivative works based on the Hatsune Miku character on the Internet provided that they are not for commercial use) encouraged the production of music, and also made it possible to collaborate on and share music. For example, sometimes if one user (called a “P”, an abbreviation of “producer”) creates a song and posts it on Nico Nico Douga, a completely different user can add original graphics and video and repost it—and sometimes an artistic-minded P might create an initial illustration and post a video first.

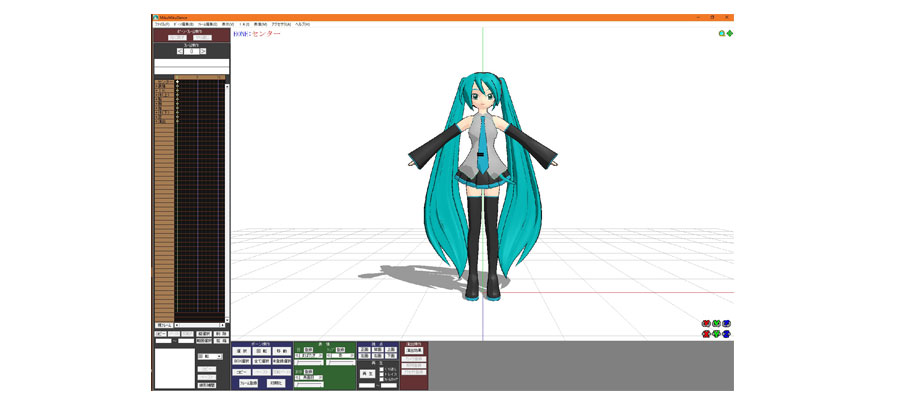

Aside from illustrations, there is a wide range of other kinds of videos including the odottemita (tried dancing) type, where a dance is added to a song, and utattemita (tried singing), in which the vocals are replaced with real singing. There is also the free software MikuMikuDance[fig.5], developed by Yu Higuchi and released in 2008, which lets the user create 3D CG movies of Hatsune Miku, and the numerous video posts created using this software. In the otaku market of the 90’s, “it has become a general strategy to create character settings first, followed by works and projects, including the stories” (6). Hatsune Miku was created in this environment of fan-culture that makes up the pivot of Japanese subculture. Looking back on the situation at the time when Hatsune Miku appeared on Nico Nico Douga, one well-known P, Kz, says:

Fig.5. MikuMikuDance screenshot

Fig.5. MikuMikuDance screenshot

“When I made that song [= ‘Tell Your World’], I was also making it for the members of the community from around 2007, who experienced a one-of-a-kind flourishing of activity based largely around Nico Nico Douga when Hatsune Miku appeared in 2007. Rather than a hymn for the current age, I’d say that we, including me as the one who posted it, had something you could call a ‘playground.’ […] I think that the presence of Hatsune Miku made connections between people. They say that the Internet functions as a hub between people, and I think that the Hatsune Miku character pushed that further. I myself didn’t know any illustrators or vocalists, but through Hatsune Miku as a hub, I found myself among all kinds of people.” (7)

In this way, people connected by the “hub” formed groups, and later hit songs with play counts of over 10 million appeared, with some members of the P community using their success to become professional composers and musicians.

From the “Playground” to Media Franchising

Hatsune Miku’s popularity did not stop at the Internet, and eventually she would expand her activities to a variety of fields. In 2009, the first installment of the Project DIVA game series released, gaining new fans, and in particular, many people were awestruck by the first live concert held on March 9, 2010 (the choice of March 9, or 3/9, reflects Japanese wordplay that can stand for both “Miku” and “thank you”). In the concert Hatsune Miku danced and performed alongside real musicians just like a real person (though projected in 3D against a translucent screen). This was the beginning of 2.5D.

In the following year, a performance was held in the United States on July 2, 2011, marking the moment that Hatsune Miku became known across the world. Professional artists well-known in Japan also started to take inspiration from Hatsune Miku. The Vocaloid Opera “The End” (2012) by Keiichiro Shibuya and “Symphony Ihatov” (2012) by Isao Tomita (d. 2016; a Keio University alumnus who worked on numerous title songs for anime based on Tezuka works) featured Miku as a soloist(8). There are also countless examples of media franchising, such as karaoke song distribution, novelizations of songs, stage performances, and more, which are beyond listing here.

Hatsune Miku will also see her 10th anniversary in 2017—though she remains forever 16. The singer of the “playground” (9) Kz discussed continues to split and duplicate herself, and is now ubiquitous. Additionally, while the software has seen numerous version updates, Hatsune Miku shoulders the fate of a pioneering technology, in that the closer her singing voice gets to that of a human’s, the more her special qualities as a Vocaloid are eliminated. That is to say, it has already become difficult to interpret and discuss her in a definitive manner. As such, in the following steps, we will consider the appeal of Hatsune Miku as a technology at the time of her birth. However, before we do so, I would like to examine a past Miku from a different time and culture, and see where it separates from the future Miku.

© Keio University

Comments