The Astro Boy Problem and Immaturity

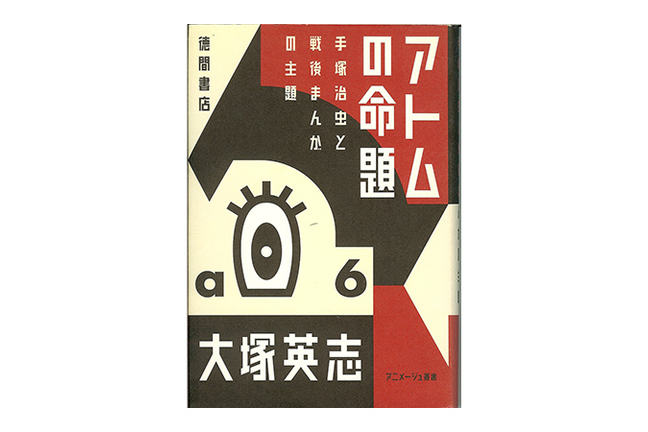

Atomu no meidai (The Astro Boy Problem), written by the critic Eiji Otsuka in 2003, and later the subject of many works in response, has become an essential work to consider when discussing Astro Boy, and Japanese manga and anime as well.

What is the Astro Boy Problem?

Otsuka explains the Astro Boy Problem as follows:

Astro Boy is a “human reincarnation.” However, his robotic body is inorganic—artificial—and does not grow up. He has a soul just like a human, but he does not grow up. That is the fate Astro Boy shoulders. The role of this Astro Boy character is an extremely critical self-reference of the methods of Tezuka manga, in which a character is dressed in artificial, unrealistic “codes,” but has a “heart” One might say that this self-reference was created by the Astro Boy character. […] Tezuka used “codes” to depict life. However, the Disney code that was originally devised for drawing “stuffed animal” characters is ill-suited for depicting living, growing bodies. Tezuka manga, within the context of post-war and occupation-period manga, struggled against this “contradiction,” but the character template for Astro Boy, where the code is a body that does not grow up because it is artificial, is a self-reference to the limitations of manga methods of expression due to the “codes” that Tezuka became aware of, and at the same time, signifies the coming into existence of the theme that underlies the history of post-war manga (1).

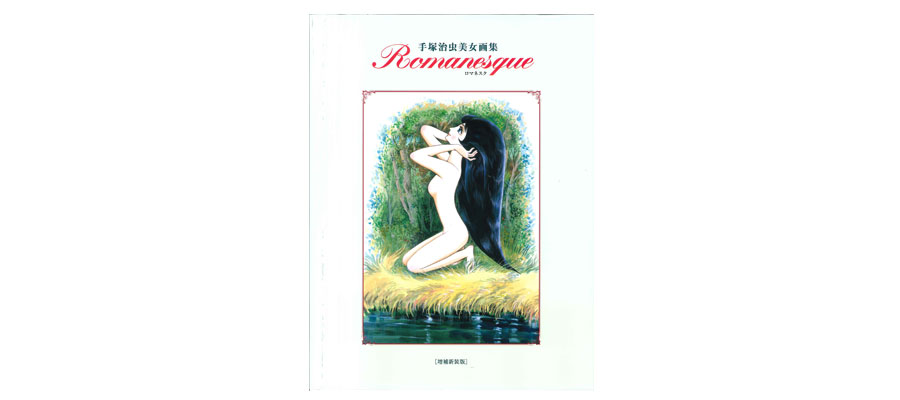

During the war, Tezuka took inspiration from Disney works, and from there, searched for his unique method of expression in manga—in other words, he constructed his characters. However, just as Mickey Mouse may be crushed in one scene and revived in the next frame, “stuffed toy,” cute bodies cannot be injured, or die. That is to say that they lack the corporeality, or reality, of living bodies. As the impression one gets of his hairstyle suggests, Astro Boy has a cute body that is also inherited from Mickey. However, Tezuka gave this body made from “an unrealistic ‘code’” a heart —life— and had it play a role in human drama. Life signifies death and sexuality. As such, Astro Boy may die many times in the story, and Tezuka-styled characters emanate an eros[fig.1] — this potential was demonstrated among other authors from the 1980s. However, this coexistence of real and unreal engenders the contradiction that the characters “cannot grow up,” and this troubles Astro Boy. The actions of Dr. Boynton, who discarded Astro Boy, reiterate this in the course of the story. And according to Otsuka, this form of Astro Boy is a self-reference to the manga form of expression pioneered by Tezuka himself.

Fig.1. Tezuka Osamu Bijo Gashu Romanesque, hand-writing work, cover page, by TEZUKA Osamu, Fukkoku dot com 2003

Available at Amazon

Fig.1. Tezuka Osamu Bijo Gashu Romanesque, hand-writing work, cover page, by TEZUKA Osamu, Fukkoku dot com 2003

Available at Amazon

The Role of Technology in Tezuka’s Characters

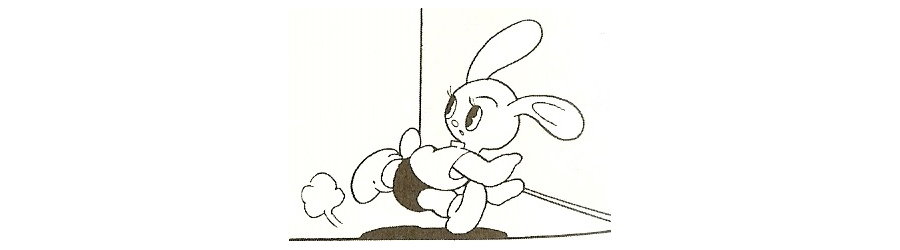

At this point, one understands that it is technology that brings consistency to the coexistence of the unreal and the real. There are several prototypes for Astro Boy; one of these is Mimio[fig.2] from Chiteikoku no kaijin (1948). Mimio is a rabbit that has been granted intelligence through the power of science—in other words, he is a rabbit that has become human. To quote Otsuka again:

Fig.2. Mimio - Chiteikoku no kaijin Maho-yashiki, p.27, by TEZUKA Osamu, Kodansha Tezuka Osamu Bunko Zenshu, 2010

Fig.2. Mimio - Chiteikoku no kaijin Maho-yashiki, p.27, by TEZUKA Osamu, Kodansha Tezuka Osamu Bunko Zenshu, 2010

Tezuka used “science” to give life to the Disney-styled, two-legged characters that spoke like people in the worlds of his work. The scientific realism that was sought in wartime manga triumphed in Tezuka manga, not as a realistic, accurate portrayal of science, but as a redefinition of manga inventions in terms of scientism (2).

In the words of Leiji Matsumoto, the Second World War was a “scientific war,” and in manga for children at the time, depictions of “scientific realism” were sought as a national policy. After the war, Tezuka used this scientism to realize his own manga form of expression. Astro Boy has an artificial body created by science and technology, and so he can remain cute while being harmed (no blood or organs come out), he can die—sometimes Astro Boy takes his head off, or stops operating—his electronic brain gives him a heart and mind, and originally, Dr. Boynton succeeded in birthing him without a woman, so perhaps this is a reflection of the desire of Tezuka himself to create a character. However, the price of this genesis is that Astro Boy is forbidden to mature.

Is Astro Boy, Who Cannot Grow Up, a Symbol of Postwar Japan?

The main point of Otsuka’s Astro Boy theory is that this immaturity coincides with the state of Japan at the time, and represents it. In 1951, right at the time when Ambassador Atom (where Astro Boy first appeared) was being serialized in magazines, the United States and Japan signed The Treaty of Peace with Japan and The Security Treaty Between the United States and Japan. In Ambassador Atom, the people of Earth and immigrants from space (presumed to be what is now called a multiverse, and so the immigrants from space are other versions of the people of Earth. For example, the relationship of Astor and Astro Boy is duplicated) come into conflict over the right of residence on Earth, and Astro Boy is selected to be an ambassador to mediate, as he “is neither a person of Earth nor an alien/ so he can settle things for both sides peacefully.” In order to start peace talks, Astro Boy offers his own, “child’s,” head(fig.3), and after this outlandish action succeeds and peace is later established, the aliens send him an adult’s face to wear, with the message “Let us meet again as adults.”

Fig.3. Ambassador Astro Boy offers a child’s head - Astro Boy, vol.1, p. 94, by TEZUKA Osamu, Kobunsha-bunko Comic Series 1995

Fig.3. Ambassador Astro Boy offers a child’s head - Astro Boy, vol.1, p. 94, by TEZUKA Osamu, Kobunsha-bunko Comic Series 1995

In this way, it is clearly no exaggeration to say that Ambassador Atom was very much an allegory of the peace between the United States and Japan, for an occupation-period Japan, likened by MacArthur to “a boy of twelve” in terms of the maturity of its democracy (3).

To what extent post-war Japan identifies with this immaturity is beyond the scope of this essay, as is the question of its conduct. However, it is certain that when Tezuka used the rationality of the discourse of technology to give life to an artificial body that does not grow while maintaining a sense of reality, or in other words, created an artificial human, a character, “postwar manga, on one hand, internalized the themes of ‘life’ and ‘death’, becoming literature, and on the other hand, evolved into sexual pornography through ‘moe’-style anime imagery” (4). Japanese people, and later people across the world, became obsessed with erotic, cute characters and their human drama as they worried, felt pain, and died. The reason why Japanese manga and anime does not exist in any other culture, and has an originality that can rival that of the United States’ Hollywood and Disney, is because of the contradiction between these real hearts and minds and unreal bodies. If the contradiction within postwar Japan, immaturity, pervades Japanese subculture, then perhaps the child of science Tezuka created and the problem he faces is the origin of the entire Japanese subculture.

Comments